Research

Learning (Animal & Machine)

I’m interested broadly in learning — but my research has focused along two main lines: representation learning for science, and applications to juvenile songbird learning

Representation learning for science

How do we build models that learn useful representations for scientists? Generally, these models need to:

- capture hidden structure in data,

- be (relatively) easy to interpret, and

- be relatively easy to train

I’ve focused on those first two points explicitly (and the third implicitly) throughout my PhD.

Modeling of animal vocalizations with Ouroboros

Structured biophysical models offer powerful and often highly interpretable explanations of behavior due to their limited numbers of parameters with real-world interpretations. However, it is often computationally intensive to search for good parameters for these models and simulate them effectively, raising challenges in scaling these models to large datasets. Conversely, deep neural networks fit very well to large datasets but are much more difficult to interpret. Dr. John Pearson and I (in work in preparation) demonstrate that we can combine these two modeling strategies to learn representations constrained by biophysical models using deep neural networks. In the latent space of this model, learning-related changes manifest as simple changes in parameter space while corresponding to complex spectral changes in vocalizations, validating that control over this parameter space allows for control of much more complicated changes in behavioral output space.

Low-dimensional latent variable modeling with QLVMs

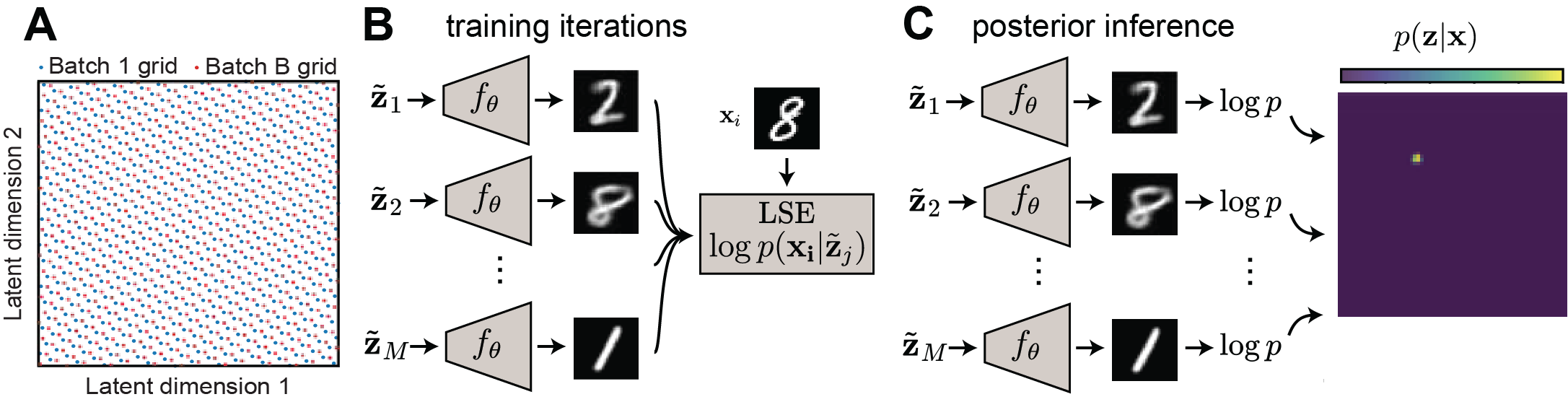

Dr. Alex Williams and I introduced Quasi-Monte Carlo Latent Variable Models (in this paper), providing an alternative set of models that can be directly visualized and analyzed without sacrificing model quality. These models allow direct approximation of the log data evidence, decoding from the latent space, tractable posterior calculation, analysis of decoder Jacobian, and analyses such unsupervised clustering (using mean-shift clustering) — all attributes highly conducive to scientific analyses.

Reproducible latent variable modeling with R-VAEs

Deep LVMs are notoriously dependent on their initialization, with many latent representations viewed as equivalent under their training objectives. We developed a method aimed at forcing VAEs to learn the same latent representations across different training runs. This model can closely mathc latent spaces trained on the same dataset across runs using a relatively small number of “anchor” points. This paper can be found here.

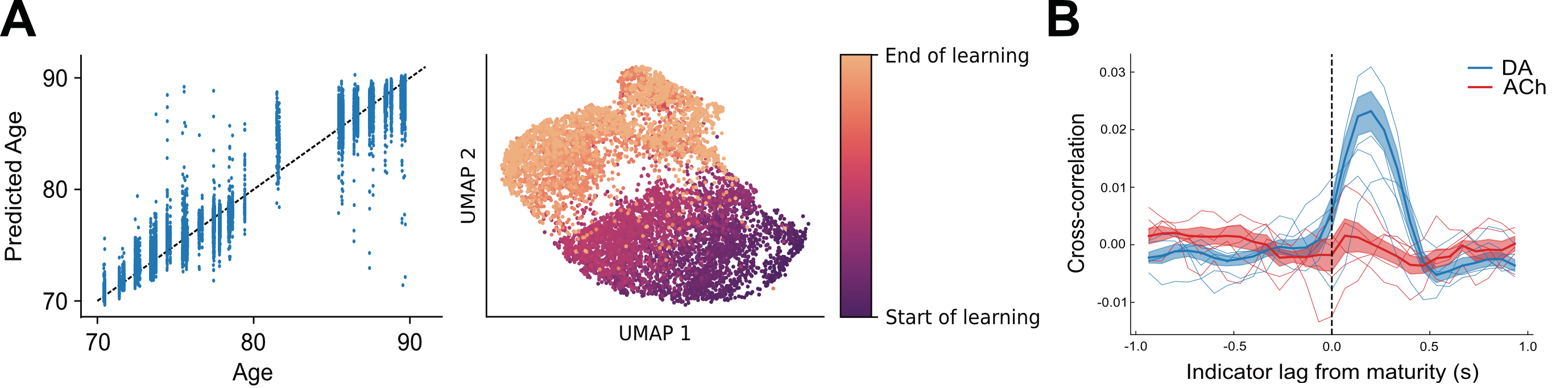

Applications to juvenile songbird learning

In a recent paper with the Mooney lab at Duke, investigating dopaminergic reinforcement of song, we used VAE-based metrics to probe the link between song quality and dopamine release in the zebra finch song basal ganglia. In this work, we confirm dopamine’s evaluative role in self-reinforced learning. I am additionally applying our Ouroboros model to a separate vocal learning dataset (work in prep) to how calcium release in the song basal ganglia reflects learning.